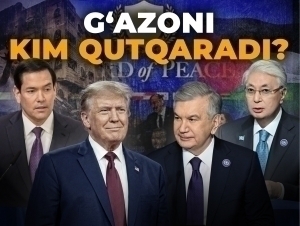

“Peace-loving” Trump or the temptation of black gold

Review

−

30 October 2025 4811 8 minutes

“Make love, not war!”

While the world remains preoccupied with the Russia–Ukraine conflict, a new war seems to be brewing in the Western Hemisphere. U.S. President Donald Trump appears intent on returning his country to its traditional role as the “world’s policeman.”

But is the same Donald Trump—who once hinted at being worthy of the Nobel Peace Prize—now planning a war against Venezuela? So, who is truly the “peace-seeking leader”?

On October 23, President Trump announced that he might authorize a ground assault against drug traffickers operating from Venezuela. This would effectively mean sending U.S. troops into the country. Given the longstanding tensions between the two nations, aggravated by various conflicts, this escalation could eventually lead to open warfare.

According to recent reports, on October 24, U.S. forces blew up a ship in international waters believed to be carrying narcotics from Venezuela. Six people were reportedly killed in the explosion. Evidence allegedly linked the vessel to a drug cartel, though the details have not been made public.

That same morning, U.S. Secretary of War Pete Hegseth announced the latest strike, claiming that the targeted ship in the Caribbean Sea was operated by the Tren de Aragua, a criminal and terrorist organization involved in drug trafficking. Since early September, the Trump administration has carried out ten such strikes on suspected drug-smuggling vessels, resulting in 43 reported deaths.

Despite this, Washington’s threats are only intensifying. By October 25, the U.S. had deployed the world’s largest aircraft carrier, the Gerald R. Ford, to the Caribbean basin.

“Our choice is peace, eternal peace. Please, stop this foolish war!” Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro pleaded in response to the growing threat.

Historical tension

Relations between the United States and South American countries have rarely been harmonious. For decades, Washington viewed the Caribbean basin and neighboring regions as its “backyard,” consistently exerting influence over their domestic policies. In 1933, under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor Policy,” some degree of autonomy was granted to Latin American nations. However, the onset of the Cold War and the fight against communism reignited U.S. interference in the region. Although the end of the Cold War somewhat eased tensions, many South American states remained dependent on the United States in various sectors.

The current strain in U.S.–Venezuela relations began in 1999 with the rise of Hugo Chávez. Initially, Chávez maintained friendly ties with Washington and promised democratic reforms and anti-corruption measures. But the failed coup attempt against him in 2002, allegedly backed by U.S. interests, drastically changed the dynamic. Though the coup collapsed, suspicions of American involvement pushed Chávez to distance his government from Washington’s influence.

Soon after, he redirected Venezuela’s oil exports from the U.S. to Russia and China, labeling the Bush administration an “imperialist power,” while Washington accused Chávez of authoritarianism. From then on, a deep rift separated the two nations.

Following Chávez’s death in 2013, Nicolás Maduro continued his predecessor’s policy of distancing Venezuela from the U.S. and strengthening ties with “anti-American” allies such as Russia, Iran, and China. Naturally, this angered Washington, which imposed heavy sanctions on Caracas and backed the Venezuelan opposition. After disputed elections in 2019, the U.S. recognized opposition leader Juan Guaidó as interim president, effectively severing diplomatic relations.

Under Joe Biden, relations slightly improved, with reduced sanctions and renewed diplomatic contact. However, the 2024 Venezuelan presidential elections—marred by accusations of power usurpation by Maduro—alongside Trump’s return to the White House in November, have reignited tensions once again.

These strained relations are not just political but also rooted in geopolitics and economics. Venezuela holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves and some of the biggest gold deposits. Unsurprisingly, the U.S. is reluctant to let such resources, located practically in its backyard, fall under the control of rival powers.

By the 1920s, Chevron—one of America’s largest oil corporations—had begun exploration in Venezuela, particularly in the Maracaibo Gulf and Orinoco Belt. The extracted oil was sold to Asia, Latin America, the U.S., and even within Venezuela itself. But when President Chávez launched a nationalization campaign of the oil industry, Washington reacted sharply, and bilateral relations deteriorated further.

At the same time, independent environmental groups criticized Chevron for its ecological impact. Poorly managed drilling operations caused oil leaks, abandoned wells, and severe water and soil pollution. International organizations such as EarthRights International and OilWatch Latin America even filed testimonies with the United Nations, leading to the temporary suspension of Chevron’s Venezuelan operations.

Meanwhile, the growing weakness of state institutions in Colombia and Venezuela in the late 20th century allowed drug cartels to gain political influence. Due to limited local markets, the cartels sought new buyers abroad, increasing the volume of narcotics trafficked into neighboring countries. The U.S., under the pretext of combating drug smuggling, began exerting heavy pressure on the Venezuelan government.

As a result, political and economic disputes have brought U.S.–Venezuela relations to the brink. Although no open war has yet broken out, the U.S. military has repeatedly attacked Venezuelan vessels in recent months.

The impact of the U.S. offensive

According to The Washington Post, President Trump has authorized the CIA to conduct covert operations in Venezuela. Online reports claim that Venezuelan forces have detained several CIA-hired mercenaries preparing a false-flag attack. Reuters also reported that the agents were allegedly plotting to carry out a staged assault.

Meanwhile, LatinTimes suggested that the situation had become far more serious, with U.S. intelligence reportedly targeting the Venezuelan president himself. The report stated that one of Maduro’s pilots had been contacted multiple times by a U.S. agent via messaging apps, offering him a large sum of money and “the eternal love of his people” if he diverted the president’s plane to Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, or Guantánamo Bay. The pilot refused and blocked the contact after their September exchange. In addition, the U.S. has long offered a $50 million bounty for information leading to Maduro’s arrest.

The war on drug cartels has long extended to Maduro’s government itself. His continued grip on power, widespread poverty, and food shortages have fueled domestic discontent. The awarding of the Nobel Peace Prize to opposition leader María Machado drew global attention to the country’s ongoing struggle for justice.

Washington’s consistent support for the opposition suggests that if the U.S. launches a ground invasion, its primary goal will be to depose Maduro and install a pro-American figure—most likely from the opposition ranks. In the short term, this could restore a semblance of democracy, improve living conditions, and bring temporary peace. However, any leader installed by Washington would have to prioritize U.S. interests, with major decisions subject to Pentagon approval.

Moreover, large-scale exploitation of Venezuela’s natural resources would inevitably follow.

According to The Wall Street Journal, Trump has already granted Chevron a license to resume oil extraction in Venezuela. If Washington succeeds, it will gain unrestricted access to the country’s resources. Jeffrey Sachs, director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, has argued that the U.S. campaign against Venezuela has little to do with drug trafficking, but rather with securing control over its vast oil reserves.

Simultaneously, Trump’s new sanctions on Russian oil companies indicate a return to old geopolitical games. Having recently imposed restrictions on Lukoil and Rosneft, the U.S. is pushing the world to stop buying Russian oil under the pretext of “promoting peace.” In reality, replacing Russian oil with Venezuelan supplies would bring substantial profits to Washington.

In the bigger picture, the Trump administration’s campaign against “narcotics and undemocratic regimes” appears to be an effort to reclaim an “old and precious toy”—oil. While the rest of the world competes in technological innovation, the MAGA movement seems determined to revive a decades-old struggle for control of energy resources.

Temur Suvonov