80 years since World War II: Soldiers, workers, weapons, food, and money taken from Uzbekistan

Review

−

09 May 2025 24807 8 minutes

One-third of Uzbekistan’s population was mobilized during World War II, a conflict in which an estimated 70–80 million people lost their lives. More than 1.5 million evacuees were relocated to the country during this period. Like much of the world, Uzbekistan suffered immense losses during the war. Under the brutal and unjust policies of Stalin, the Uzbek people endured the hardships of yet another global conflict that reached far beyond Europe.

From Uzbekistan to World War...

While World War II is widely recognized as having begun in 1939 with Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland under Adolf Hitler, the roots of the conflict trace back to unresolved tensions following World War I. Initially confined to Europe, the war entered Soviet territory on June 22, 1941, when Nazi Germany launched a surprise attack on the USSR. From that day on, the Soviet Union, including Uzbekistan, endured four years of hardship during what became known as the "Great Patriotic War."

Based on analysis of global archives and newly uncovered data, approximately 1,950,700 people from Uzbekistan were mobilized for the war effort—roughly one in every three Uzbeks. Of those, over 538,000 were killed, more than 158,000 went missing, over 870,000 were wounded, and more than 60,000 returned home with disabilities.

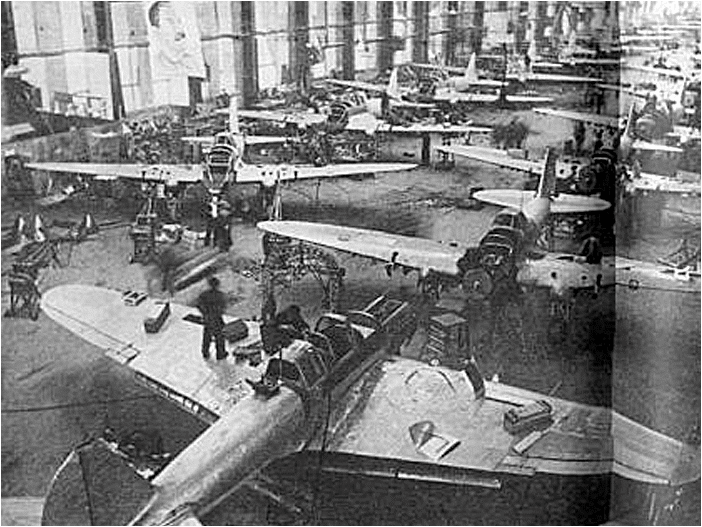

Military equipment, money, and food supplied by Uzbekistan

In addition to providing manpower, Uzbekistan played a crucial role in supplying the front with essential resources, including military, food, and light industry products.

During the war, much of Uzbekistan’s industrial capacity was redirected toward producing military equipment. According to available data, Uzbekistan supplied the front with 2,100 aircraft, 17,342 aircraft engines, 2,318,000 aircraft bombs, around 60,000 pieces of military-chemical equipment, 22 million mines, 560,000 shells, 1 million grenades, 330,000 parachutes, over 100,000 kilometers of military wire, 4,500 mine detectors, 2,861,000 pairs of army boots, more than 59,000 horses, and numerous other forms of military hardware.

Despite severe wartime conditions, Uzbekistan became a vital supply base for the Soviet front lines. The country established new production sectors including aircraft and instrument manufacturing, weapons and ammunition, and electrical equipment to support wartime needs.

In addition, the Uzbek people continuously sent essential goods and financial support to soldiers on the front lines.

According to the book-album "Uzbekistan During the Second World War", between 1941 and 1943, citizens of Uzbekistan voluntarily donated over 475 million rubles to the national defense fund, along with 22 million rubles’ worth of valuable personal belongings.

Uzbekistan also made exceptional efforts to provide food for the war effort. The country delivered 1,282,000 tons of grain, 482,000 tons of potatoes and vegetables, thousands of tons of melons, and both dried and fresh fruits.

According to historian Professor Hamid Ziyoev, over the four years of war, Uzbekistan supplied 4,806,000 tons of cotton, 54,067 tons of cocoons, 1,066,000 tons of grain, 195,000 tons of rice, 108,000 tons of potatoes, 374,000 tons of vegetables and fresh fruits, 35,289 tons of dried fruits, 57,444 tons of grapes, 1,593,000 tons of meat, and 5,286,000 pieces of animal hides.

Uzbeks who were not thanked for their labor

A large number of Uzbeks were mobilized to military-industrial zones in Russia as part of the "Workers’ Battalion," which included 155,000 people. Most of them came from rural areas and, lacking knowledge of the Russian language and unaccustomed to the harsh climate, endured immense hardship. They suffered due to severe living conditions and worked in worn-out clothing, facing cold, hunger, and poor treatment.

Professor Hamid Ziyoev, who was a young man during the war and witnessed these events firsthand, recalled the fate of many Uzbek laborers sent to Russia:

“When I was being treated in a Siberian hospital, I personally saw people from our homeland begging. Their hair and beards had grown long, their clothes were patched and dirty. According to them, many died of hunger and disease. The men of the Workers’ Battalion labored half-starved in industrial plants and mines in Novosibirsk, Moscow, Tula, Bashkortostan, Tatarstan, and other regions. Many were buried without shrouds, far from their homeland.”

It must be emphasized that these Uzbek workers, sent to military-industrial enterprises as manual laborers, were not given the respect or recognition their service deserved. Despite the extreme conditions, many of them over-fulfilled the quotas set before them. However, wage discrimination was evident. One worker at the Kirov plant shared the following:

“If the workers at the Kharkov plant fulfill the quota by 100 percent, they receive 1,000 grams of bread. Even if I fulfill it by 150 percent, I only receive 700 grams of bread.”

According to researcher Obidjon Alimov, monthly wages for Central Asian workers were very low, and they were poorly nourished.

Many of those brought from Uzbekistan were forced to live inside factories, without proper housing. Workers at a metallurgical plant in the Chelyabinsk region recalled that Uzbek laborers at the metal foundry could not understand orders due to the language barrier and often performed their tasks incorrectly. They would raise their hands in apology, be beaten for failing to complete work, and be deprived of their bread rations. They suffered from extremely poor hygiene, a lack of medicine and warm clothing, and frequent illness. In the early stages, the deceased were buried in white shrouds according to Islamic customs, but later, as fabric ran out, even this practice was abandoned.

These laborers have since been referred to by researchers as “unarmed soldiers”:

“The ‘unarmed soldiers,’ who lacked professional skills for industrial work and did not know the Russian language, still labored to the limit of their strength for victory, despite enduring humiliation, illness, and hunger.”

This historical account illustrates a harsh contrast: while Uzbeks welcomed over 1.5 million evacuees from war zones, cared for 250,000 orphans, and shared their last pieces of bread with them, they themselves were denied shelter, clothing, and food during their time in military-industrial enterprises—and were subjected to deeply unfair treatment.

Woman who waited for her life partner, a young man who killed 13 fascists, and 3 brothers who never returned: War heroes

The image of a woman waiting a lifetime for her husband, often portrayed in foreign films, was also a reality for thousands of Uzbek women whose husbands went to war and never returned. One such woman was Chinni Aya Kamalova, the widow of Soli Rajabov from Kashkadarya. Only a few months after their wedding, Soli Rajabov was drafted, leaving his 18-year-old bride, Chinnikhan, behind. Though the war ended and peace returned, Soli never came home. Yet Chinni Aya waited for him until the end of her life.

Millions of Uzbek sons died or were killed on the frontlines of the brutal war. One such hero was 18-year-old Shodi Shoimov, who reportedly killed 13 fascists in hand-to-hand combat. A wrestler serving in the 385th Rifle Division, Shoimov encountered Nazi soldiers on June 27, 1944, during the crossing of the Dnieper River in Belarus. He succumbed to his injuries a day later. Posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, Shodi Shoimov left no photographs behind. Years later, a bust of him was reconstructed using a photo of his sister Tilovat. That image is now preserved in a museum in Dashkovka, Belarus.

In truth, every Uzbek who served at the front or supported the war effort from behind the lines was a hero, regardless of whether they received medals or titles. There was not a single home that remained untouched by the war. In many families, more than one child was mobilized. Such was the fate of the Hasanov family from Baysun. Father Hasan and mother Bibisora, who raised five sons, sent three of them to war—one after the other. When Bibisora asked the chairman of the collective farm why all three sons were being taken, he replied, “They are being taken away too many times.” The three brothers—Bozor, Bobonazar, and Khidirnazar—left unmarried and never returned.

“My father used to say that our grandmother Bibisora turned to drinking after her three sons never came back,” recalls Oyimgul Hasanova, the daughter of their surviving brother, Chori Hasanov.

According to her, a villager who returned from the war once saw one of the brothers at the front. The brother told him that he was serving in military intelligence and was about to embark on an important mission. “We may never see each other again,” he reportedly said—and they never did.

World that never stops fighting

The world, having endured World War I—with its 20 million deaths—and World War II—with more than 80 million casualties—continues to witness ongoing conflicts. The Middle East remains unstable with the persistent conflict between Gaza and Israel, and war-torn Syria. The Russia-Ukraine conflict shows no signs of resolution after three years. Rising tensions between India and Pakistan also threaten regional stability. And this is only part of the global picture.

“Politicians start wars, the rich sell weapons, and the people send their children. The war ends. Politicians reach an agreement. The rich become wealthier. But the people never get their children back.”

Live

All