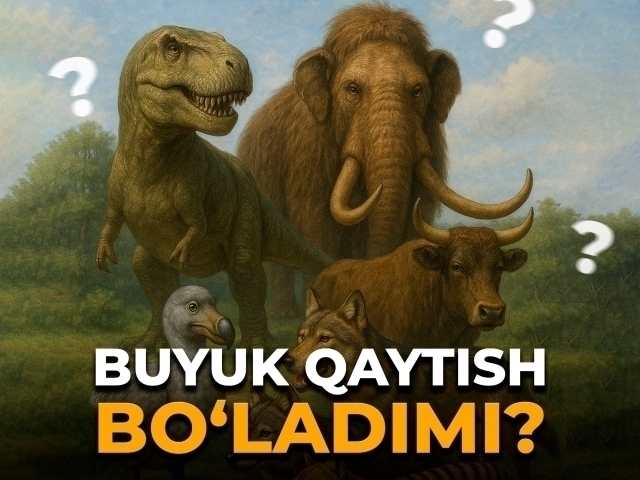

From mammoths to dinosaurs: Who’s next after dire wolves?

Interesting

−

18 April 2025 11295 7 minutes

Dire wolves, extinct 12,000 years ago, were recently "resurrected" in the United States. This raises a fundamental question: is it possible to bring back mammoths, dinosaurs, and other extinct species, and reintroduce them to the wild? What are the next ambitions of biotechnologists capable of resurrecting extinct species from bone remains?

The "resurrection" of dire wolves: What’s the real deal?

Scientists have recently begun experimenting with the concept of resurrecting extinct species, ranging from the dire wolves to woolly mammoths. Colossal Biosciences, an American biotech company, recently brought back a copy of the dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus) using genes extracted from a 72,000-year-old skull and a 13,000-year-old tooth. These wolves, made famous by the TV series Game of Thrones, were revived by mixing ancient DNA with the eggs of a modern gray wolf and implanting them into surrogate mothers, which were large breed dogs. The genome editing process involved 20 changes, focusing on characteristics such as a large body, strong muscles, and white fur.

However, as science progresses, a crucial question remains: how authentic must the "resurrection" be to be considered a true revival? If only portions of the extinct species' genome are used and the rest is supplemented by modern substitutes, can this really be called "resurrection," or is it simply a genetic copy? This is a critical point that many biotechnologists are grappling with.

Colossal Biosciences, for example, relies on incomplete genetic blueprints—ancient DNA—and then uses a powerful genome editing tool called CRISPR to introduce changes to the genome of closely related living species. The animals born from this process may resemble the extinct species in appearance and some behavior but won’t be genetically identical. In reality, these creatures are hybrids, mosaics, or functional substitutes, not pure revivals.

"Resurrection" or just a copy?

When people think of “de-extinction,” they often picture the perfection seen in Jurassic World, where dinosaurs are brought back to life. But, unlike the movies, synthetic biology uses techniques such as selective breeding, cloning, and increasingly sophisticated genome editing.

For example, scientists have used selective breeding to recreate animals that resemble the wild aurochs, the ancestor of modern cattle. In 2003, Spanish biotechnologists cloned a Pyrenean ibex that went extinct in 2000, but sadly, it died moments after birth.

All three methods—selective breeding, cloning, and genome editing—share the same goal: to restore a lost species. However, bioinformatics expert Timothy Hearn points out that these animals aren’t genetic clones of the original species. Instead, they are modern organisms designed to resemble the function or appearance of their ancestors.

Do "resurrected" dire wolves look like the originals?

According to Nick Rollens, an associate professor at the University of Otago in New Zealand, the so-called "resurrected" dire wolves are not true dire wolves—they are merely similar in appearance.

“What Colossal created is actually a gray wolf with characteristics similar to a dire wolf,” Rollens explained.

To create these wolves, scientists used DNA extracted from two ancient dire wolves: one from a 13,000-year-old tooth found in Ohio, and the other from a 72,000-year-old inner ear bone found in Idaho. With this DNA, they reconstructed a partial genome of the dire wolf and compared it with the genomes of its closest living relatives—wolves, jackals, and foxes.

However, research by David Mech, a senior researcher at the U.S. Geological Survey, suggests that the dire wolf was not even a true wolf. From an evolutionary standpoint, dire wolves (Aenocyon dirus) diverged from modern wolves about 6 million years ago, making them a distinct group from today's gray wolves.

According to Philip Seddon, a professor of zoology at the University of Otago, dire wolves belong to a separate genus altogether, meaning they were a completely different species. While the revived animals may look similar, genetically, they are much closer to modern wolves than they are to the ancient dire wolves.

Efforts to bring back the mammoths

Colossal, a leading biotech company, has announced plans to revive the woolly mammoth by 2028, using mammoth DNA and cells from Asian elephants. The company aims to create a mammoth-like creature by integrating DNA from a baby mammoth preserved in permafrost and using a surrogate Asian elephant mother. The $10.2 billion project has already raised $435 million in funding.

In an interview with "The Conversation", bioinformatics expert Timothy Hearn discussed the challenges of the project:

“The goal is to create an Asian elephant that can fulfill the ecological role once played by mammoths and is adapted to cold environments. However, mammoths and Asian elephants diverged hundreds of thousands of years ago, and there are about 1.5 million genetic differences between them. Editing all these differences is currently not feasible. As a result, scientists are focusing on editing only a few dozen genes related to key traits such as cold tolerance, fat storage, and fur growth.”

Hearn went on to explain that despite humans and chimpanzees sharing about 98.8% of their genetic material, the physical and behavioral differences between the two species are profound. If small genetic differences can cause such significant disparities, what might we expect from editing just a portion of the genetic differences between mammoths and Asian elephants?

Biotech’s ambitious projects go beyond mammoths and dire wolves

Colossal isn’t stopping at mammoths. The company is also working on reviving the thylacine, also known as the Tasmanian tiger, a predatory marsupial that lived on the Australian mainland, Tasmania, and New Guinea until its extinction in 1936. Scientists are using the white-footed mouse as the genetic foundation for this project. Their goal is to re-engineer the mouse genome to express characteristics unique to the thylacine. Additionally, the team is developing an artificial uterus to carry the resurrected fetus.

Another project being pursued by biologists aims to bring back the dodo, a flightless bird that went extinct on the island of Mauritius in the 15th century. The Nicobar pigeon, a close relative of the dodo, is being used as the genetic basis for this project.

Will dinosaurs return?

Humans have always been fascinated by dinosaurs, and if it were possible, scientists would likely have attempted to bring them back by now. While scientific studies have explored this idea, the DNA of dinosaurs, which disappeared 66 million years ago due to a massive asteroid impact, has not been preserved. Only traces of tissue and the shapes of blood cells have been found.

Recently, a 45-million-year-old mosquito fossil was discovered containing red pigment, hinting that traces of blood might be found in other insects from the dinosaur era. However, this discovery does not guarantee the presence of DNA. In 2015, scientists found compounds similar to red blood cells in a dinosaur bone, but they were unable to find any preserved DNA, as DNA is quickly destroyed by sunlight, water, and time.

To date, the oldest DNA discovered is about 1 million years old. To revive dinosaurs, DNA would need to be much older—approximately 65 to 66 times older than any DNA discovered to date. If such DNA were found, it would have to be a complete genome, containing all the genetic information needed to create a living dinosaur. In the event of an attempt to resurrect dinosaurs, the closest living relatives—birds and crocodiles—could be used for their DNA, as they are genetically linked to dinosaurs. However, for now, this remains a fascinating but distant scientific dream.

Live

All