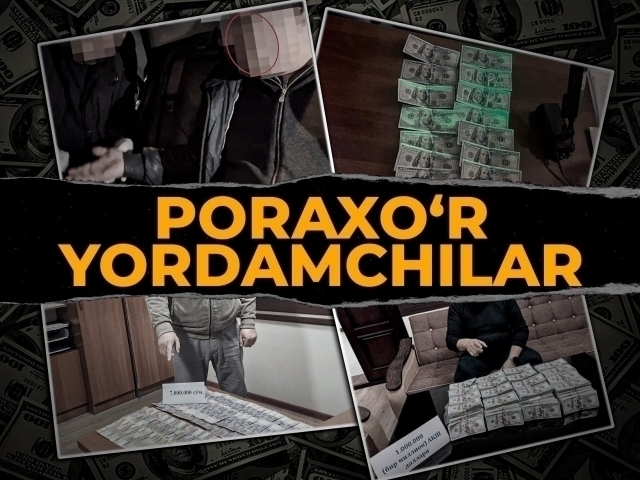

Bribery among governor’s assistants

Review

−

03 February 2025 12675 8 minutes

The assistants to regional governors appear to be making headlines more frequently, but not for commendable reasons. According to the Anti-Corruption Agency, governor’s assistants were involved in corruption cases 309 times in 2024 alone. Their presence in corruption statistics has become so significant that they are now separately mentioned in official reports. This troubling trend aligns with concerns raised by President Shavkat Mirziyoyev in 2022, when he addressed the issue in a video conference:

“It is also a very sad situation that some assistants of the governors in the regions are begging, saying, ‘I will give you a loan, subsidy, land.’”

Despite these warnings, corruption among governor’s assistants has persisted. The new year has already brought fresh scandals. In mid-January, during a law enforcement operation, an assistant mayor of a neighborhood citizens' assembly in the Uchtepa district was caught accepting a $30,000 bribe. The money was allegedly received in exchange for securing a land registration through influential contacts. Notably, this official had previously been convicted three times under the Criminal Code for embezzlement (Article 167), fraud (Article 168), and abuse of power (Article 205). The issue extends beyond assistants—if they are implicated, it is no surprise that even deputy mayors are involved.

In November last year, a joint operation by the State Security Service and the Prosecutor General’s Office led to the arrest of the deputy mayor of Chirchik. He was caught demanding $2 million from a citizen, having already received $1 million through his driver. The deputy mayor had allegedly promised to secure 20 hectares of land from the governor’s reserve, on the condition that the citizen invest $40 million. Perhaps the most troubling aspect of these corruption cases is the involvement of law enforcement officials themselves. One particularly shocking case occurred in early 2024 when a prosecutor in Bukhara was caught accepting a $100,000 bribe. The incident was so serious that the President personally addressed it:

“The prosecutor of the Kagon district was caught with $100,000. Why am I telling the people this? The prosecutor himself is engaging in such actions—if he is supposed to be a fighter against crime but turns out to be a thief, then who can we trust with our problems?”

In August, the court reviewed the criminal case against Bakhodir Gulomov, the prosecutor whom the President labeled a “thief.” He was found guilty under Article 168, Part 4, Clause “a” (Fraud) and Article 28,211, Part 3, Clause “a” (Abuse of authority by officials in a non-governmental commercial or other non-governmental organization) of the Criminal Code. As a result, he was sentenced to 15 years in prison and banned from working in prosecutorial bodies for three years.

Corruption: A trap for officials

Corruption often thrives due to weak government institutions, ineffective laws, and inadequate wages, pushing officials to exploit their positions for personal gain. Economist Jamshid Muslimov highlights the damaging effects of corruption, particularly its impact on economic development.

“The economy flourishes only where there are fair and transparent 'rules of the game' for everyone. Corruption distorts the investment climate and stifles economic growth. As a result, unemployment rises, and incomes decline. The misappropriation of state funds disrupts key sectors such as infrastructure, education, and healthcare,” he explains.

When an official engages in corruption for the first time, they effectively place a noose around their own neck, handing control to others. To cover up their crime, they continue offering bribes throughout their career, allowing corruption to spread like a spider’s web. According to Sherzod Saparov, head of the Anti-Corruption Agency’s press service, a key challenge in combating corruption is the lack of willpower among officials.

“The absence of strong political will and the reluctance of institutional leaders to embrace change significantly complicate the fight against corruption,” Saparov told QALAMPIR.UZ.

He further noted that Uzbekistan aims to develop its own anti-corruption model, drawing from the experiences of countries such as the United States, Singapore, China, various European nations, South Korea, and Japan.

Public participation plays a crucial role in combating corruption.

“For this to be effective, people must be well aware of their rights and ready to defend them. The media plays a vital role in mobilizing society against corruption. Transparency, public oversight, and reporting corruption cases are among the most effective measures,” explains economist Jamshid Muslimov.

How does Uzbekistan punish corrupt officials?

Under the Criminal Code of the Republic of Uzbekistan, corrupt officials can face prison sentences ranging from ten to fifteen years. But are these penalties sufficient for crimes that undermine the state’s economy and society? According to lawyer Davron Yakubov, the issue lies not in the laws themselves but in their enforcement.

“The gap is not in the legal framework but in its practical application. Moreover, the fight against corruption mainly targets lower-ranking officials. If it does not extend to the highest echelons of power, it creates the impression that these efforts are merely symbolic,” Yakubov explains.

In 2021, President Shavkat Mirziyoyev issued a decree titled “On Measures to Create an Environment of Uncompromising Attitude Towards Corruption, Sharply Reduce Corruption Factors in State and Public Governance, and Expand Public Participation.” The decree instructed the Anti-Corruption Agency to establish a public register of corrupt officials and introduce a mandatory property declaration system. However, years have passed, and these measures have yet to be fully implemented. As a result, individuals previously convicted of corruption are being reinstated to government positions.

As the saying goes, “Once learned, never forgotten.” Many of these individuals go on to reoffend. At a Legislative Chamber meeting on September 10 last year, Deputy Umida Rakhmonova highlighted this issue, revealing that 566 former corruption convicts had been readmitted to the civil service—only to engage in corruption again. She attributed this to the absence of an open register and questioned Akmal Burkhanov, Director of the Anti-Corruption Agency, about its status.

Burkhanov responded that an initial draft law had been developed in early 2022, coordinated with ministries and departments, and submitted to the Presidential Administration earlier this year.

“I believe we will submit this law for your consideration by the end of this month,” he said.

However, more than four months have passed since then. When QALAMPIR.UZ inquired about the project’s status, Agency representative Sherzod Saparov confirmed that work is still ongoing, promising that an official announcement will be made once it is finalized.

The delay raises concerns about the effectiveness of anti-corruption reforms, highlighting the urgent need for concrete action to ensure accountability at all levels of government.

See one and be grateful, see another and reflect...

History has repeatedly shown that corruption can dismantle even the most powerful states from within. The fall of the Western Roman Empire—renowned for its culture, architecture, and rich history—was largely driven by corruption. Contemporary historians documented that officials prioritized personal gain over the empire’s well-being, misallocated tax revenues, and failed to provide adequate military funding. These internal weaknesses made it impossible to resist barbarian invasions, ultimately leading to the empire’s collapse.

Similar cases exist in the modern world. Consider Venezuela, one of the ten richest countries in natural resources. Despite its wealth, the South American nation struggles with widespread poverty. The root cause? Corruption. Venezuela ranks 177th out of 180 countries in global corruption indices. Bribery, nepotism, and lawlessness are deeply entrenched, forcing millions of Venezuelans to flee to neighboring countries like Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru. Meanwhile, any protests against the government are met with ruthless suppression, leading to international sanctions from multiple European nations.

Humanity is unique in its ability to learn from past mistakes. As the saying goes, “See one and be grateful, see another and reflect.” Like many other countries, Uzbekistan is striving to combat corruption by promoting two key initiatives: an open electronic registry of convicted corrupt officials and a mandatory asset declaration for public servants. However, their implementation continues to face delays.

Without a publicly accessible registry of individuals convicted of corruption, there is no guarantee that former offenders won’t return to public office and repeat their crimes. Similarly, without mandatory income declarations for civil servants, it remains impossible to track the origins of their wealth. After all, not being caught taking a bribe does not mean one isn’t receiving them. These two measures are essential and must complement each other. The only question is: when will they finally be implemented?

Iqbol Ergashova