From homes to classrooms: How Uzbekistan plans to shield children from abuse

Review

−

03 May 2025 10103 7 minutes

According to the new law “On the Protection of Children from All Forms of Violence,” which is expected to come into force on May 15, children who are victims of violence will now receive protection orders. The families of such children will be assessed and monitored, and if deemed necessary, the child may be removed from the family. A legislative initiative is also being introduced that would expel from the profession those teachers who “give themselves too much freedom” in educational institutions.

What else does this law entail, and what are the current statistics on children’s rights in Uzbekistan? This article will explore those questions and present insights from experts.

Six out of ten children under the age of 14 in Uzbekistan are subjected to psychological violence, and three to physical violence...

A study conducted in 2022 in cooperation with UNICEF (the United Nations Children’s Fund) revealed that some forms of violence are still socially accepted in Uzbek society. According to the findings, 31 percent of children aged 1–14 are raised using non-violent methods. Meanwhile, 29 percent of children in that age group are subjected to some form of physical punishment, and 4 percent experience severe punishment. Additionally, 60 percent experience psychological violence, and 62 percent are raised using methods that contain elements of violence. Moreover, 11 percent of mothers and other caregivers believe that children should be physically punished.

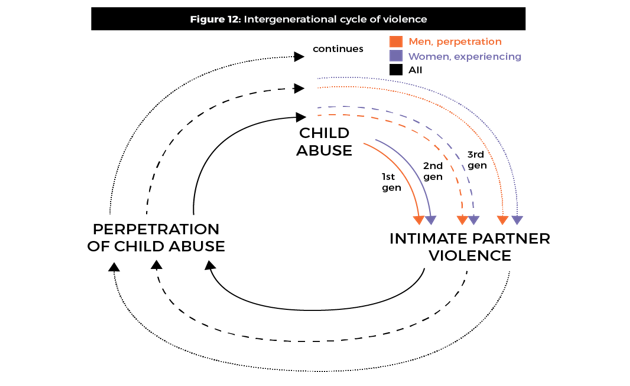

Interestingly, 40.7 percent of Uzbek women surveyed said they justify the use of physical punishment on themselves in certain situations. Experts suggest that this mindset stems from these women having grown up in environments where violence was normalized. Children raised in violent households often replicate such behavior toward their own children or spouses in the future. This contributes to rising divorce rates and the continued cycle of violence in various forms. As a result, a tense and nervous atmosphere is created in society. Looking deeper into the problem, it becomes apparent that economic and social factors help foster environments where family violence can thrive.

According to UNICEF, one adolescent dies every seven minutes globally as a result of violence. Around 176 million children witness physical abuse against their mothers. Fifteen million girls aged 15 to 19 have already experienced sexual violence. Three out of four children worldwide are exposed to physical violence by people around them, often under the guise of “nurture.” These numbers highlight the widespread violation of children’s rights.

What situations are considered violence?

Uzbekistan has been a party to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child since 1994. This international commitment requires the country to ensure all children’s rights are protected and that violence against them is prevented. In May last year, the Legislative Chamber passed a new law on the protection of children’s rights. This law was approved by President Shavkat Mirziyoyev in November and is scheduled to take effect in May 2025. Comprising 51 articles, the law governs all relations related to protecting children from violence.

Article 3 of the law defines violence against children as:

“Any intentional act (or omission) that violates a child’s life, health, sexual integrity, honor, dignity, or other legally protected rights and freedoms, causes or is likely to cause physical or mental suffering, and contradicts their basic needs — including acts carried out using telecommunications networks and the Internet — shall be recognized as violence against children.”

Taking a child…

Uzbeks, who form the majority population in the region and have high birth rates, are often referred to as a “people of children.” However, the above statistics alone reflect the dire state of children’s rights within families. Moreover, numerous videos on social networks show children being used as “tools of interaction” between quarreling spouses.

In none of the following tragic cases — where a father in Samarkand killed his three children, a man in Namangan murdered his wife and three children with an axe before setting himself on fire, or a woman in Tashkent jumped from the ninth floor with her three children — were the children at fault. These horrors were outcomes of adult conflicts. The new law seeks to address such issues by enabling the removal of children from such households.

Article 28 of the law stipulates that when a child’s life or health is under immediate threat due to violence, the following measures shall be taken:

- administrative detention of the perpetrator of violence by legal procedures and application of procedural coercive measures;

- issuance of a protection order;

- and removal of the child from the care of parents (or a parent) or other custodians if violence has occurred or is likely to occur.

Child removal is also covered under Article 38 of the law. According to this article, the authorized state body has the right to take immediate measures to remove a child whose life or health is in imminent danger. Afterward, the child may be placed with a parent who can ensure the child’s best interests, with relatives, with a person willing to care for the child, with individuals registered with the authorized state body, in a medical facility if the child has health issues, or in a specialized shelter for victims of violence.

Laylo Fayzimurodova, Deputy Head of the Department for Development and Monitoring of Services for Children in Difficult Situations at the Ministry of Internal Affairs, told QALAMPIR.UZ that in such cases, the child’s family is assessed and monitored. If the parent is deemed a threat to the child's life or health, the child is removed from the home. If needed, legal documents are prepared and submitted to the court to either limit or terminate the parent’s rights. Such decisions are made solely by the court.

How does a protection order work?

Article 32 of the law regulates the issuance of protection orders. It states that a protection order valid for 30 days will be issued to a child who is a victim of violence. If the threat persists, a criminal court may extend the order’s validity to up to one year.

Failure to comply with a protection order may result in a fine of one to three times the basic calculation amount or administrative detention for up to fifteen days, as stated in Article 206 of the Code of Administrative Offenses (Failure to comply with the requirements of a protection order by a person who has committed or is inclined to commit harassment and/or violence).

This raises a critical question: how does a protection order work if the child lives under the same roof as the perpetrator? According to Fayzimurodova, the violent person may be temporarily barred from using the residence where the victim lives, or a part of it if it is shared. They may also be prohibited from approaching the child’s place of study, work, or other locations where the child may be.

A teacher who raises a hand against a child will be expelled from the profession

Article 44 of the upcoming law explicitly prohibits “beating and cursing” children in educational institutions.

According to Fayzimurodova, the Ministry of Internal Affairs has prepared a draft law proposing amendments to ensure this article is effectively implemented. These include amendments to Article 47 of the Code of Administrative Responsibility (Failure to fulfill obligations to raise and educate children), which would introduce administrative penalties for “violent educators.”

The draft also proposes to amend Article 44 of the Law “On Preschool Education and Upbringing” regarding restrictions on employment in preschool institutions and Article 15 of the Law “On the Status of a Pedagogue” concerning restrictions on pedagogical activity. Specifically, the following provisions are being added: persons held administratively liable under Article 47 of the Code of Administrative Responsibility may not engage in pedagogical activities; and it is prohibited to accept individuals into positions involving pedagogical activity if they have such a record.

At a time when social media has become a space for debate over various incidents involving teachers and students, including cases of abuse in kindergartens, it remains to be seen whether this legislative project will be approved — and if it is, whether it will adequately address the problem. However, there is little doubt that the law, which is set to come into effect soon, will spark significant public discussion.

Live

All40 gektar maydonda Yangi Jizzax shahri quriladi

03 February

Erdo'g'an Saudiyaga bordi

03 February

Putin “qora shahzoda” bilan telefonlashdi

03 February

Qashqadaryoda YPX mashinasi yonib ketdi

03 February