Underwater history: A journey to the sunken settlements

Interesting

−

20 October 2025 8300 8 minutes

The cities submerged underwater are not just myths. Many ancient coastal civilizations were engulfed by seas or oceans, leaving their streets, houses, and temples beneath the waves.

For centuries, due to the inability to explore beneath the water, knowledge about such places remained mythical. From the early 20th century onwards, advancements in oceanography and marine sciences opened the way for underwater archaeology. This allowed scientists to map sites, collect artifacts, and bring clarity to the stories of drowned cities.

Some of the earliest coastal settlements were submerged due to climate change. Using geomorphological, sedimentary, and paleontological data, scientists determined that during the peak of the last Ice Age—approximately 30,000 to 20,000 years ago—the sea level was nearly 130 meters lower than it is today. As the Ice Age ended and polar ice caps melted, sea levels rose sharply. Many ancient settlements built along coasts were flooded and abandoned. The project “Archaeology and Landscapes of Submerged Ancient Cities” recently identified about 2,600 such drowned sites across 19 countries. Among them is France’s Cosquer Cave near Marseille, famous for its ancient wall paintings. The cave’s entrance now lies around 30 meters below sea level.

Unstable ground

People often refer to Earth as “solid ground,” but this is far from reality. In fact, the planet is in a constant process of geological movement, continuously changing through natural destruction and renewal. Tectonic plate movements can cause earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, and other seismic events that shake, erode, liquefy, or even submerge the land.

History has witnessed numerous such geological transformations. In ancient times, people attributed these events to divine punishment. Today, however, scientists seek rational explanations for the natural phenomena that once sent cities beneath the sea.

Seismic activity has repeatedly led to the disappearance of coastal regions and entire cities. A strong earthquake or the tsunamis that follow can wipe out cities completely. For example, in 373 BC, the Greek city of Helike met this fate. Seven centuries later, in 365 AD, one of the most powerful earthquakes in the history of the Mediterranean struck the island of Crete. Estimated at magnitude 8.3, it triggered massive tsunamis that devastated coastal cities such as Alexandria in Egypt and Apollonia in present-day Libya.

More widespread than such violent tremors is subsidence—the gradual sinking of the Earth’s crust due to seismic or volcanic activity. As land subsides, the sea advances inland, swallowing any structures in its path. These natural processes caused the total or partial disappearance of many coastal settlements throughout history. Since the remains and ruins lay underwater, archaeologists were unable to study them in detail until the last century.

The Mediterranean basin, including the Black Sea, contains numerous submerged monuments. Today, these drowned sites have become “hunting grounds” for modern underwater archaeologists. Researchers use SONAR (sound navigation and ranging systems to detect and measure the distance of underwater objects), robotics, 3D scanning, and underwater cameras to explore them.

Pavlopetri: The oldest sunken city

Located on the southern Peloponnese peninsula, Pavlopetri dates back to around 3500 BC as a Neolithic settlement and later became an important trading center of Ancient Greece. The Aegean region’s vulnerability to earthquakes and tsunamis led to the city’s gradual submergence. Buildings near the coast were destroyed by sea storms and tsunamis, and over 3,000 years ago, rising sea levels in the Mediterranean left the city underwater.

For centuries, the remains of Pavlopetri lay hidden under thick sand at a depth of about four meters off the coast of Laconia. In recent decades, water currents and climate changes began eroding the sediment that had concealed the city. The ruins were first identified in 1967 by British oceanographer Nicholas Flemming during a survey of sea-level changes. A year later, he returned with a group of students to study and map the site, identifying around 15 buildings, courtyards, a street network, and a two-chambered tomb.

In 2009, a joint effort between archaeologists and the Greek government resumed excavations. By this time, underwater archaeology tools and techniques had advanced far beyond those of the 1960s. The team used robotics, SONAR mapping, and advanced graphics technology to study the site, successfully revealing the ancient underwater city by 2013. Covering about 2.5 hectares, Pavlopetri featured three main streets linking nearly 50 rectangular buildings, each with open courtyards.

Phanagoria: A city beneath the Black Sea

Around 540 BC, Ionian Greeks fleeing the Persian Empire built a city on the Taman Peninsula, near present-day Krasnodar, Russia. They named it Phanagoria after one of the settlers. The city prospered through maritime trade and became wealthy. By the 4th century BC, it was part of the Bosporan Kingdom—a Greek-Scythian state that ruled much of the region—and eventually became its eastern capital. Later, under Roman influence, Phanagoria continued to thrive.

In the early centuries AD, Phanagoria’s fate changed. Intense seismic activity and mud volcanoes weakened the ground beneath the city, causing it to sink. When the Black Sea waters advanced, part of the city was submerged, while the remaining sections were destroyed during invasions and lost their significance.

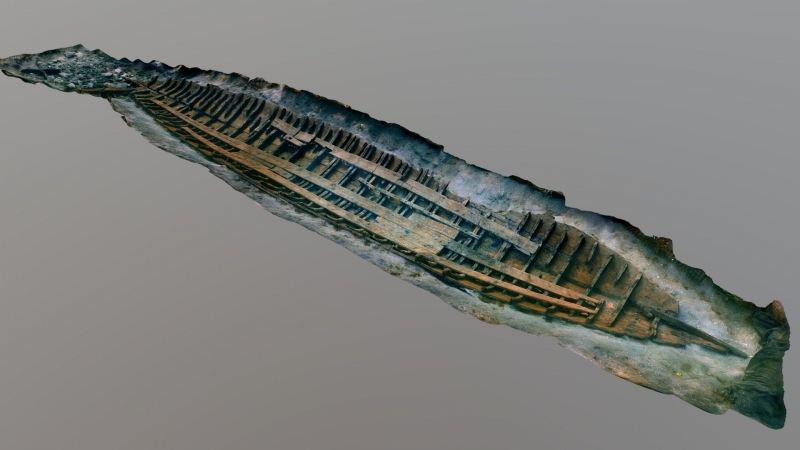

Phanagoria’s ruins were discovered in the 1800s, though only the land-based areas were studied. In the 1950s, researchers confirmed that about 60 hectares of the ancient city lay underwater. As technology advanced, discoveries multiplied. In 2004, archaeologists unearthed the remains of a large coastal structure believed to be a lighthouse or watchtower from the 3rd–4th centuries AD. In 2012, they identified the port area of the city, along with a remarkably well-preserved small warship dating back to the 1st century BC.

Heracleion and Canopus: Egypt’s lost ports

The two most important ancient Egyptian ports, Heracleion and Canopus, sank beneath the waters of the Abu Qir Bay around 1,200 years ago. Scholars believe both cities, located in the Nile Delta, were submerged due to rising sea levels and continuous seismic activity. Heracleion was a major trading hub, serving as a gateway for goods arriving from across the Mediterranean. First mentioned in sources from the 8th century BC, it declined gradually after Alexandria emerged as a dominant trade center in 331 BC.

In 2000, underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio and the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology discovered the ruins of Heracleion. Among the findings were the remains of the famous Temple of Amun-Gereb, its outer walls, and three colossal statues over 4.5 meters tall at the entrance. More than two decades of exploration have since revealed much about the city’s history. Canals, small shrines, numerous shipwrecks, and hundreds of stone anchors indicate that it once was a bustling trading hub for Greek merchants.

Canopus, meanwhile, was an important religious center during Egypt’s Ptolemaic era. It was home to a massive temple dedicated to Serapis, a deity combining attributes of both Greek and Egyptian gods. Pilgrims from across the ancient world traveled to Canopus to worship there. In 1933, Egyptian scholar Prince Omar Toussoun conducted the first archaeological survey of the site, following reports from fishermen and an English pilot. In 1999, Goddio’s team rediscovered the site during their exploration of Abu Qir Bay, confirming it as the lost city of Canopus.

Epidaurus: The coastal villa

The Greek city of Epidaurus, world-renowned for its grand theater, was once one of the most important trading ports on the Argolid Peninsula. During the Roman Empire, many seaside villas were built along its coast, taking advantage of fertile lands and easy access to the sea. These settlements were centers of agriculture and production of wine, olive oil, and garum—a popular fish sauce highly valued by Romans. Though hardworking, the residents lived in comfort, as archaeological evidence reveals the presence of baths, recreation areas, and guest rooms.

In the 5th century AD, just a century after its construction, one of these villas near the Agios Vlassios Bay sank underwater. This happened due to intense seismic activity and rising sea levels in the region. In 1967, oceanographer Nicholas Flemming documented several underwater structures in the area. In 1971, archaeologist Charalambos Kritzas identified what locals called “the sunken city,” confirming it was the remains of a Roman-era coastal villa.

Located only 45 meters from the shore and 1.9 meters deep, the villa’s ruins consist of three rooms. One served as a large storage area where fragments of nearly 20 large ceramic vessels used for storing and fermenting wine were found. The second room appeared to be a wine-pressing area, while the third might have been a bathhouse.

Live

All